With the proliferation of the Internet, online information has become a crucial aspect of our daily lives. From researching for academic purposes to browsing for leisure activities, we rely heavily on the Internet to provide us with a vast array of information. However, despite the Internet's convenience, searching for information can be challenging, and users may experience various problems during the process.

ABLE is a comprehensive tool that combines the functionality of a browser with a vast knowledge base. Our mission is to revolutionize the browsing experience for individuals who regularly work with information, conduct research, and utilize the Internet as an integral part of their daily routines.

To better understand the behavior of users when searching for information online, we at ABLE conducted an in-lab study. Our primary objective was to validate our assumptions and gather further insights for designing an improved browsing experience. In this blog post, we will share the details of our study, including our methodology, goals, observations, and a part of the solution.

Our study aimed to answer several questions, including:

While we relied on the research conducted by Nielsen Norman Group (NNG, 2021), we wanted to gather our results and gain additional context of the experience.

To attain this goal, we conducted five moderated search sessions with participants to gain insights into their search and browsing behavior.

Before the study, we formulated assumptions regarding common problems faced by users when using browsers and search engines. We utilized session recordings and the think-aloud method to validate these assumptions and gain additional insights.

We recruited participants with prior experience using the Internet and search engines in their daily routines. As part of the study, we provided them with a piece of paper, a pen, and access to various programs on a computer, such as Notepad and Google Docs.

Learning for future studies: As we conducted our research, we realized the importance of conducting similar studies on participants' own computers and in their natural environment. Providing them with lab computers resulted in a lack of familiarity with the tools they typically use, which made it difficult to observe their natural workflow accurately.

We took a task from a study (Gwizdka, 2017) and conducted recording sessions. The session consisted of two assignments, each with four questions that the respondents had to find the answer to on the Internet while commenting on their actions and thoughts aloud.

During the sessions, we recorded every action the participants took. We then created a table with second-by-second transcriptions, including action highlighting, to analyze the results and gain insights into their browsing process and the challenges they encountered.

During our study, we gained insights into various browsing behaviors and identified common problems that participants encountered. Here are the most valuable observations we made.

The participants commonly opened multiple search results in new tabs, reviewing them individually before closing unnecessary tabs. Typically, they ended up with 3-7 tabs with relevant information related to each task. However, when attempting to formulate their answers, they frequently had to revisit the information they found and struggled to remember which tabs contained the most valuable information. It often led to confusion and wasted time.

However, the participants tended to prioritize highly relevant search results by immediately reading them while setting aside less relevant results in browser tabs for later evaluation.

The participants tended to scan web pages instead of reading the entire text, relying on headings and structured content such as tables or bullet or numbered lists. They often used page search functions (Ctrl+F) to find specific information on a page quickly. Once they found relevant information, they read the content closely to extract more specific details.

Based on these observations, we confirmed the assumption that when users search for information online, their primary focus is on the information itself rather than the source or webpage it is hosted on. The evaluation of the context and source comes later in the process after users have found relevant information that meets their needs.

Interestingly, we observed that participants tended to highlight text and move the mouse while reading.

The participants tended to avoid clicking on internal links within web pages to find more specific information or references unless they encountered difficulty finding information through Google.

Another intriguing discovery from our study was that participants modified their search queries when they switched to searching for fundamentally different information or needed clarification on specific terms. However, if the search results did not provide the necessary information, they corrected or supplemented their search queries to get more accurate results.

Our study also showed that searching for the primary information about a topic takes less time than searching for specific details. Respondents spent most of their session time searching for definitions of terms and abbreviations.

Finally, we noticed that the respondents' search quality decreased when they became tired, while those more competent in the specified field spent more time uncovering better information.

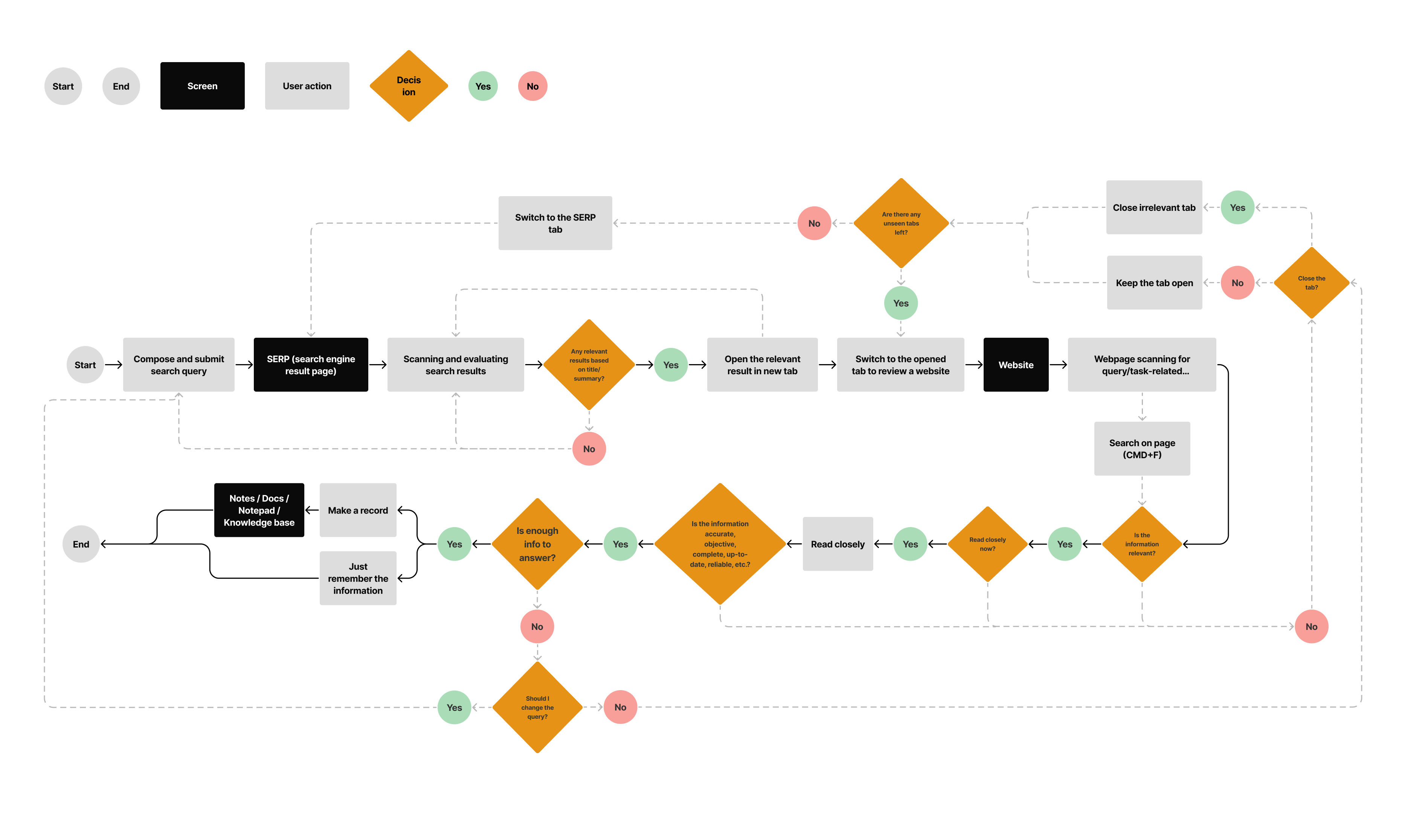

Based on our analysis of the participants' online search behavior, we validated a generalized browsing experience process. The scheme below outlines the typical process participants underwent when searching for information.

This validated scheme has provided us with a deeper understanding of how people interact with browsers and has yielded valuable insights into how we can enhance the browsing experience for users in ABLE.

During the design and testing phases, our team faced a significant challenge due to the complexity of our solutions. Additionally, the browsing experience involves a wide range of user input, making it difficult to test using simple interactive prototypes. However, we overcame these challenges by focusing on designing and testing specific aspects and flows of the user experience, such as navigation and supportive features. Through this process, we identified many solutions that were not viable and required further iteration.

Over the course of nearly six months, we engaged in a process of iterative design, continuously refining our solutions for selected aspects of the user experience. We then tested each prototype with a small focus group of users, seeking to validate our solutions and gather valuable feedback for analysis.

To test the overall experience, we recognized the need to develop a proof of concept (POC) that included only the necessary features. We committed to a long play game with developing this POC to validate the general process and provide a better browsing experience for ABLE users.

Two years after conducting this study, we are excited to announce that we will be sharing our solutions through a series of informative blog posts. These posts will detail how ABLE addresses the issues we identified in this (and other) research. One of the available posts discusses how ABLE helps users manage multiple tabs and tackle tab clutter.

We are currently in the final stages of developing the ABLE proof of concept and are preparing to conduct tests with our waitlist users in the near future. If you are interested in being among the first people to try ABLE and participate in our future studies, we encourage you to sign up for our waitlist. Your feedback and insights will be essential in helping us refine and enhance the browsing experience for our users. Thank you for your interest and support in our research endeavors.

NNG Kate Moran and Feifei Liu (2021). How People Read Online: The Eyetracking Evidence, 2nd Edition. https://www.nngroup.com/reports/how-people-read-web-eyetracking-evidence/

Gwizdka, J. (2017). I Can and So I Search More: Effects Of Memory Span On Search Behavior. CHIIR '17: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Conference Human Information Interaction and Retrieval

I hope you have enjoyed reading this article. Feel free to share, recommend and connect 🙏

Connect me on Twitter 👉 @carina_avy

And follow Able's journey on Twitter: @meet_able

Now we're building a Discord community of like-minded people, and we would be honored and delighted to see you there.